Introduction

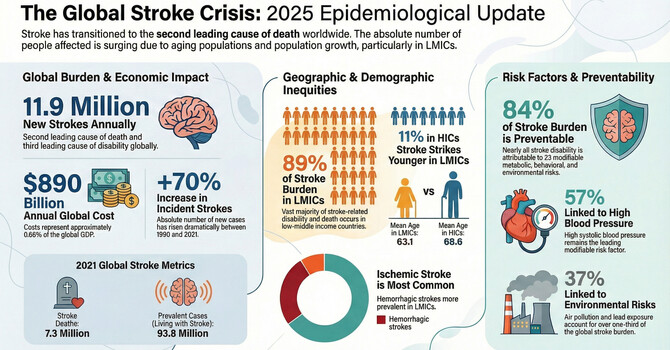

For anyone living with Parkinson's Disease (PD), the advice from doctors and physical therapists is consistent and clear: exercise is one of the most beneficial things you can do. It's a message of empowerment, suggesting that purposeful physical activity can help manage symptoms and improve quality of life. Yet, this advice presents a profound paradox. A neurological condition defined by its progressive impairment of movement requires intentional movement as one of its most powerful therapies.

This reality can be daunting. Generic recommendations to "stay active" often fail to capture the nuances and specific challenges faced by individuals with PD. The truth is, exercise for Parkinson's is not just about strengthening muscles or improving cardiovascular health; it's a sophisticated intervention that interacts with the disease on a neurological level in ways that are both surprising and incredibly hopeful.

This article moves beyond the basics to reveal four science-backed truths about exercise and Parkinson's that may change how you, your family, and your caregivers approach physical activity. These are not just tips but fundamental principles that underscore why movement is medicine for the Parkinson's brain.

1. It’s Not Just for Your Muscles—Exercise Literally Changes the Parkinson's Brain

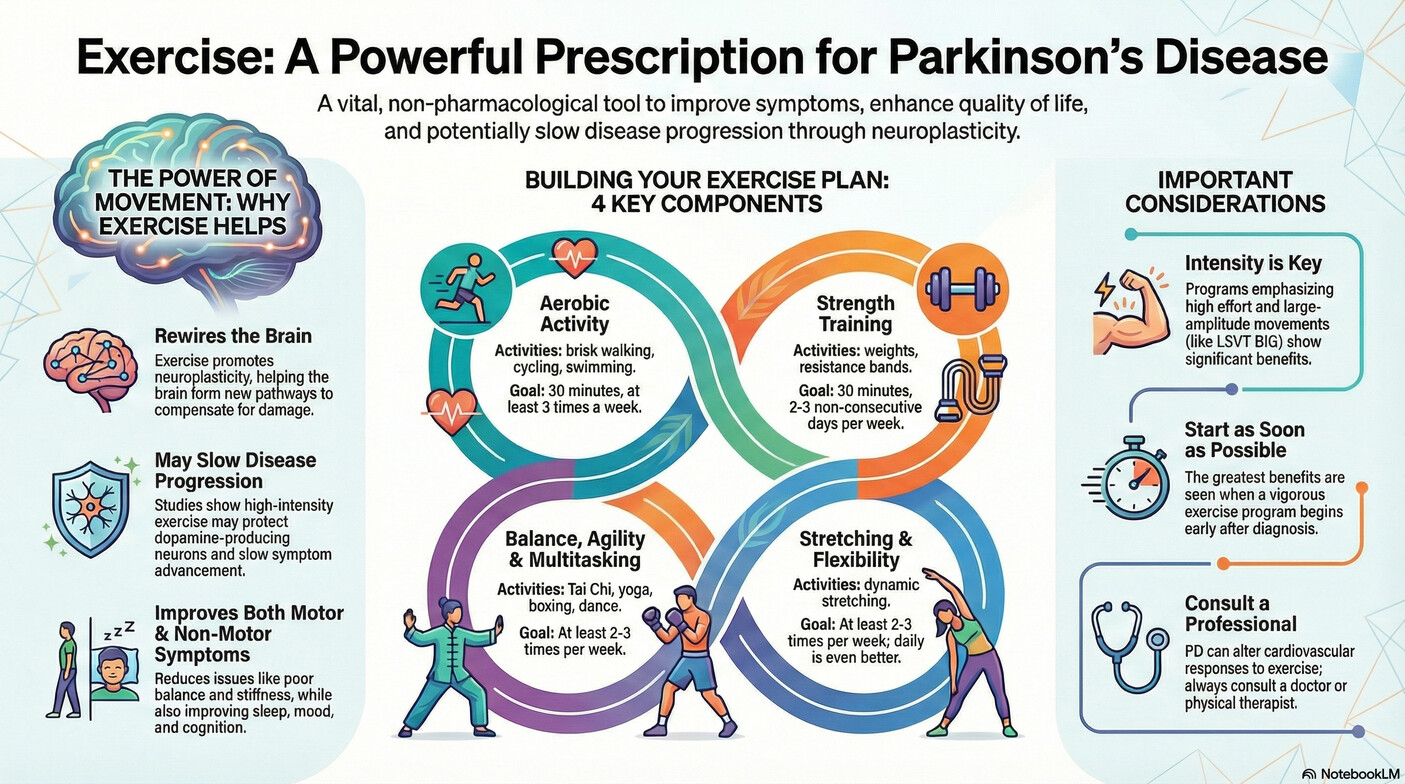

The most profound benefit of exercise in Parkinson's Disease isn't what happens from the neck down, but what happens from the neck up. This is due to a fundamental property of the brain called neuroplasticity—its remarkable ability to adapt, reorganize pathways, and create new connections in response to experience. Exercise is a powerful trigger for this process.

Scientific evidence shows that physical activity can induce these structural and functional changes in the brain. Specifically, exercise has been shown to increase the levels of crucial neurotrophic factors like Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), a protein that plays a key role in synaptic plasticity, which is essential for learning and memory.

More remarkably, research suggests that certain types of exercise can directly impact the health of the dopamine-producing neurons that are damaged by PD. A study led by Yale Medicine neurologist Dr. Sule Tinaz investigated the effects of high-intensity exercise on the brains of people with Parkinson's. The results were striking:

"We found that high-intensity interval training three times a week for six months did increase the dopaminergic signal in the brain, which suggests it might actually improve neuron function. Whatever dopamine-producing neurons still exist in Parkinsonian brains seemed to become more viable and healthier—and they produced more dopamine."

This finding is transformative. It reframes exercise from a method of simple symptom management into a potentially neuroprotective intervention. The idea that intentional physical activity could help the brain's remaining dopamine neurons function better offers a powerful and hopeful path forward, suggesting that movement can directly counter the effects of the disease at a cellular level.

2. Your Body’s Speedometer Is Off: The Paradox of Blunted Cardiovascular Response

A surprising and critical finding in Parkinson's research is that the body's cardiovascular response to exercise is often "blunted." This means that during physical activity, the heart rate and blood pressure of a person with PD may not increase as they should. Imagine driving a car where you're pushing the accelerator to the floor, but the engine can't get the gas it needs, so the speedometer barely moves. That is what can happen inside the body during exercise with PD.

While an attenuated response might indicate good physical fitness in a healthy person, in the context of PD, it can signify "decreased exercise efficiency." In practice, this means the cardiovascular system is struggling to meet the metabolic demands of the working muscles. This explains the profound, bone-deep fatigue that can make exercise feel impossible—it’s not a lack of willpower, but a physiological mismatch between effort and your body's ability to respond.

The direct consequence is that standard methods for prescribing exercise intensity can be dangerously misleading. The same autonomic dysfunction that blunts the heart rate response also causes a disconnection between real exertion and perceived exertion. A crucial study found that PD patients exercising at a moderate to vigorous intensity (60-80% of their heart rate peak) reported their level of effort as being merely between “fairly mild” to “somewhat hard.” This underscores the absolute necessity of seeking expert, PD-specific guidance over generic fitness advice that relies on perceived effort or standard heart rate zones.

3. Think Bigger (Literally): Why 'Just Walking' Isn’t Enough

While any movement is better than none, research increasingly shows that the type of exercise is crucial and that specialized, PD-specific therapies often outperform generic activity. These programs are revolutionary because they are not just about movement, but about intentionally retraining the brain's motor pathways to combat the specific deficits caused by the disease. Two of the most well-known philosophies are LSVT BIG and PWR! Moves.

- LSVT BIG: This therapy directly combats the brain's "shrinking" perception of movement by focusing on high-amplitude, repetitive, and "exaggerated movements." Its core concepts are Maximum Effort and Amplified Movements. It's like turning up the volume on movement, teaching the brain that what felt 'normal' was actually too quiet, and what feels 'too big' is actually just right. This forces the brain to recalibrate to a new, larger normal.

- PWR! Moves: This program deconstructs complex movements into four core building blocks essential for daily life, rehearsing the exact moments where Parkinson's can cause freezing or falls. Rather than just a list of exercises, it targets critical functional challenges like pushing up against gravity (PWR! Up), shifting your weight to stay balanced (PWR! Rock), turning your torso (PWR! Twist), and making transitions like stepping or getting out of a chair (PWR! Step).

Beyond these specialized programs, a wide range of other complex and varied activities have demonstrated significant benefits. Studies have shown that dancing, boxing, Tai Chi, and resistance training all help improve motor function, balance, and quality of life. The key takeaway is that the most effective exercise for Parkinson's is not just about burning calories. It's about challenging the brain to relearn movement patterns with intensity, specificity, and intentionality.

4. This Isn't a 'No Pain, No Gain' Scenario: Acknowledging the Cardiovascular Risks

While the push for high-intensity, vigorous exercise is strong, it must be balanced with a clear understanding of the unique cardiovascular risks associated with Parkinson's Disease. This knowledge is not meant to discourage exercise but to empower patients and caregivers to pursue it safely.

A significant concern is orthostatic hypotension (OH), a sudden drop in blood pressure upon standing, which affects over 40% of people with PD. Compounding this, some patients may also experience supine hypertension (high blood pressure when lying down). Because of these conditions, sudden changes in position during exercise—such as moving from the floor to standing—must be approached with caution.

The same autonomic wiring issue that blunts your heart rate during a workout is also responsible for the dangerous blood pressure drops and profound fatigue that can occur. In fact, researchers note that the inability to properly elevate blood pressure during physical activity is "a significant component of exercise intolerance." The body simply cannot generate the pressure needed to adequately perfuse the muscles and brain during exertion. This information underscores a non-negotiable rule: anyone with Parkinson's Disease must consult with a knowledgeable doctor or a physical therapist, preferably one with experience in PD, before starting or significantly changing an exercise routine. These risks can be managed effectively with a properly designed and monitored program, but they cannot be ignored.

Conclusion: The Path Forward Begins with a Single Step

The science of exercise in Parkinson's Disease paints a clear picture: this is a sophisticated, brain-changing intervention that goes far beyond general fitness. It is a targeted therapy that leverages the brain's own capacity for change to fight back against the disease. To be effective, it must be approached with specific knowledge, an emphasis on intensity and complexity, and an unwavering focus on safety.

The message is profoundly hopeful and actionable. It is never too late to start, and as experts note, "the sooner you start exercising while you have the capacity, the better." Even for those with advanced symptoms, exercises performed from a seated position or while lying down can be beneficial. Every movement, when done with purpose and intention, is a step toward better function and a healthier brain.

Knowing that every intentional movement can help your brain forge new pathways, what is the one 'big' step you will take for your health today?