Summary

-

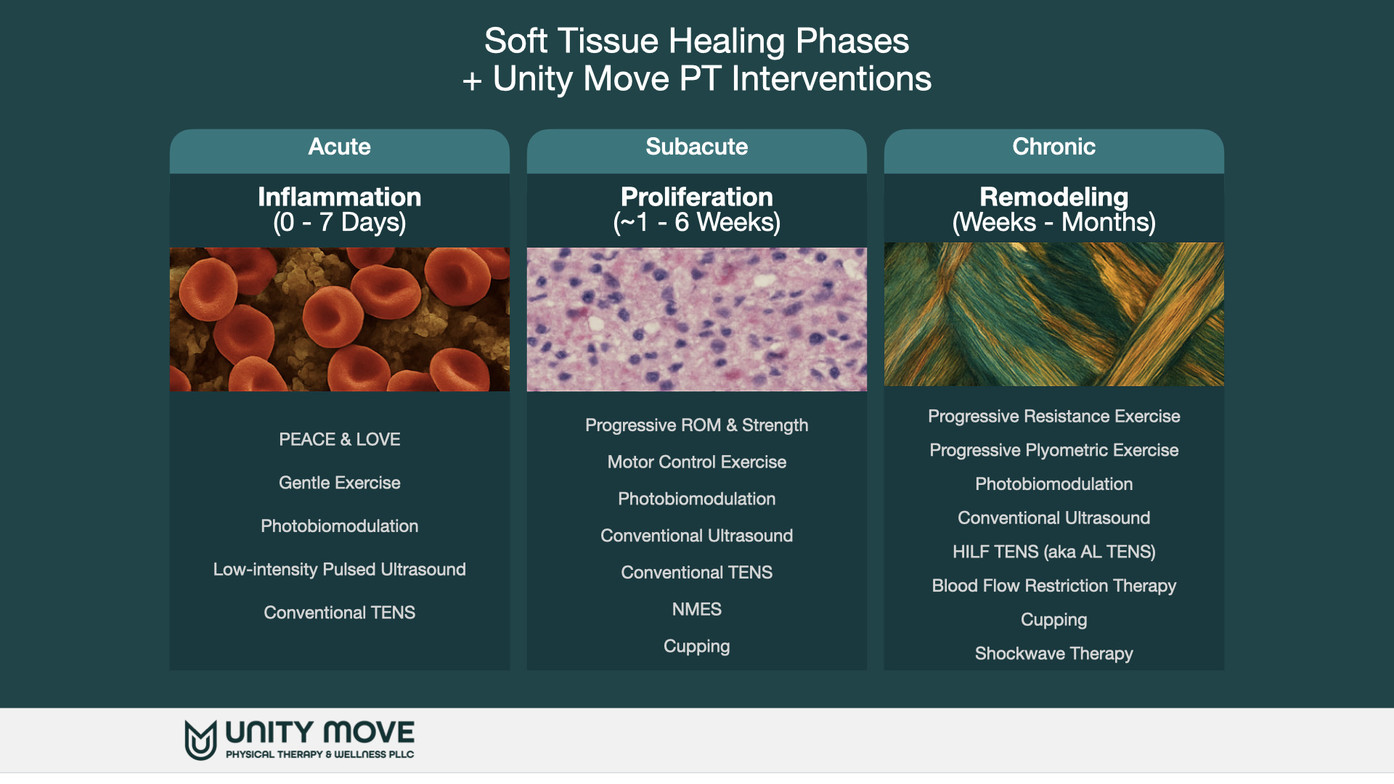

Soft-tissue healing follows overlapping biological phases: hemostasis → inflammation → proliferation → remodeling. These phases map onto clinical time frames often described as acute, subacute, and chronic. (NCBI)

-

The right plan changes by phase. Early on, protect and manage irritability; next, restore motion and begin progressive loading; later, build strength, capacity, and confidence for your goals. (British Journal of Sports Medicine)

-

Timelines vary by tissue (muscle vs. tendon vs. ligament), injury grade, age, and health factors—so use symptoms and function (not just the calendar) to progress. (PMC)

First, what counts as “soft tissue”?

-

Muscle (contractile tissue)

-

Tendon (connects muscle to bone)

-

Ligament (connects bone to bone; stabilizes joints)

-

Fascia, joint capsule, skin (supportive tissues)

Injuries are typically graded: Grade I (mild) microtears, Grade II (moderate) partial tears, and Grade III (severe) near-complete or complete tear.

The biology of healing (and how it maps to clinic time frames)

| Biological Phase | What’s happening | Typical time course* | Clinical “phase” |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemostasis | Bleeding stops; clot forms | Minutes → hours | Hyper-Acute |

| Inflammation | Clean-up + chemical signaling; swelling/warmth/tenderness are normal | ~1–7 days (can vary) | Acute |

| Proliferation | New collagen + blood vessels; early scar; tissue is weak and disorganized | ~1–6 weeks | Subacute |

| Remodeling | Collagen realigns and strengthens along stress lines | Weeks → months (sometimes up to a year for tendons/ligaments) | Chronic |

*Timelines are general; different tissues heal at different speeds. (NCBI, PMC)

How fast do different tissues tend to recover?

-

Muscle strains: often improve over weeks to a few months depending on grade. (NCBI)

-

Tendon injuries: biological remodeling is slow; functional progress typically requires months of progressive loading. (PMC)

-

Ligament sprains: healing is measurable over 6 weeks–3 months and remodeling beyond; some people have lingering laxity without targeted rehab. (PubMed)

What to do in each clinical phase

1) Acute Phase (first days to ~1–2 weeks)

Goals: Calm things down, protect tissue, and maintain whole-body movement without aggravation.

Smart moves:

-

PEACE framework right after injury: Protect (brief relative rest), Educate (what pain/swelling mean), Avoid anti-inflammatories early if possible**, Compress, Elevate.

Then LOVE as soon as tolerable: Load gradually, Optimism (expect improvement), Vascularization (light cardio that doesn’t flare symptoms), Exercise (gentle, pain-guided). (British Journal of Sports Medicine) -

Pain-guided range of motion: small, frequent, comfortable motions to prevent stiffness (e.g., ankle pumps after an ankle sprain). (JOSPT)

-

Isometrics (muscle “hold” contractions) to maintain strength without shear, if comfortable (e.g., quad sets, calf squeezes). (JOSPT)

-

Support when needed: bracing/taping for short periods to limit excessive stress, particularly with ligament sprains. (JOSPT)

Note: The goal is relative rest, not bed rest. Aim to move often within a pain-tolerable window, and avoid sharp “twinge” pain or increasing swelling after activity. (British Journal of Sports Medicine)

2) Subacute Phase (~1–6 weeks)

Goals: Restore motion, begin progressive loading, and re-establish coordination and confidence.

Smart moves:

-

Gradual stretching to patient-tolerated end range (protect healing muscle/tendon from aggressive end-range stretching early if it reproduces sharp pain). (PMC)

-

Strength progression: isometrics → light isotonics (2–3 sets, low-to-moderate load) → functional patterns (sit-to-stand, step-ups). Keep pain mild and short-lived during/after (a “traffic-light” rule helps: green ≤2/10, yellow 3–4/10 that settles within 24 h, red ≥5/10 or next-day flare). (JOSPT)

-

Motor control & balance: single-leg balance, gentle perturbations for ligament sprains to restore joint sense and stability. (JOSPT)

-

Aerobic work that doesn’t aggravate the injury (bike, brisk walk, arm ergometer). This improves blood flow and helps remodeling. (British Journal of Sports Medicine)

-

Manual therapy (as needed) to address pain and mobility limits, alongside active exercise—not instead of it. (JOSPT)

3) Chronic/Remodeling Phase (≥6 weeks to months)

Goals: Build capacity (strength, power, endurance), refine movement quality, and return to sport/work/life goals.

Smart moves:

-

Progressive resistance training to near-fatigue with good form; increase load/volume gradually (e.g., every 1–2 weeks if symptoms behave). Tendons, especially, respond to slow, heavy loading over months. (PMC)

-

Energy-storage drills when appropriate (e.g., pogo hops for lower-leg tendons) after baseline strength returns and symptoms are quiet. Tendon pain/structure don’t always align; load should track function and irritability. (British Journal of Sports Medicine)

-

Higher-level neuromuscular training: multiplanar balance, agility, change of direction for ankle/knee sprains to reduce reinjury risk. (JOSPT)

-

Graded exposure to your real goals (lifting groceries, hiking, pickleball). Increase only one variable at a time: load, speed, or volume. (British Journal of Sports Medicine)

Tissue-Specific Notes (Why Timelines Differ)

-

Muscle strains: often improve over weeks; loading through tolerated range drives alignment and strength.

-

Tendon pain: responds to consistent, progressive loading over months; adjuncts (PBM, ESWT) can help alongside a loading plan. PubMed

-

Ligament sprains: benefit from balance/neuromuscular training; current guidelines emphasize exercise/manual and advise against regular ultrasound in acute sprain. JOSPT

When to get checked right away

-

Sudden “pop” with loss of function, visible deformity

-

Night pain, fever, or spreading redness

-

Worsening numbness/weakness or giving-way

-

Non-improving sprain/strain after 2–3 weeks of smart self-care

A skilled exam clarifies what’s injured, the stage of healing, and the right load for today.

Sample week-by-week arc (illustrative, not prescriptive)

-

Weeks 0–1 (Acute): Protect, short walks, gentle ROM, isometrics, compression/elevation as needed. (British Journal of Sports Medicine)

-

Weeks 2–4 (Early Subacute): Restore full ROM, introduce light strengthening and balance drills; start easy cardio. (JOSPT)

-

Weeks 5–8 (Late Subacute): Heavier strength, functional patterns (stairs, carries), faster walking intervals. (PMC)

-

Weeks 9+ (Remodeling): Goal-specific progressions (jogging, court movement, lifting), plyometrics if appropriate. (British Journal of Sports Medicine)

What We Do at Each Stage (Unity Move PT & Wellness)

At Unity Move, your plan always centers on therapeutic exercise and manual therapy—then we add targeted physical agents to facilitate tissue healing, manage pain, and help you progress safely.

1) Acute phase (first days → ~1–2 weeks) — updated with PBM + LIPUS

Goals: Settle irritability, support early tissue biology (inflammation → proliferation), and keep you moving within comfort.

Core plan (unchanged)

-

PEACE & LOVE approach: relative protection, early pain-guided movement, gentle ROM, isometrics; avoid next-day flares. JOSPT

Adjuncts we may add at Unity Move

-

PBM (photobiomodulation, “low-level laser”)

Why: PBM modulates early inflammatory signaling and mitochondrial activity, which can reduce pain and support cellular processes involved in repair. A recent athlete-injury meta-analysis shows PBM can reduce musculoskeletal pain and may speed return to play when used alongside rehab. PMCPubMed -

LIPUS (low-intensity pulsed ultrasound)

Why: Unlike conventional therapeutic ultrasound, LIPUS uses very low intensity in pulses to create mechanical (non-thermal) signaling that, in preclinical models, enhances early collagen organization, angiogenesis, and anti-inflammatory pathways in acute tendon/ligament injuries—aiming to support the biology of healing during days 1–14. Human evidence is emerging; we use LIPUS as an adjunct to exercise/manual care when irritability is controlled. PubMedPMC -

TENS (electrical stimulation for pain)

Short-term analgesia to enable gentle motion and sleep. JOSPT -

What we skip in “acute”:

Conventional therapeutic ultrasound for acute ankle sprain (no meaningful added benefit vs active care in guidelines/Cochrane). LIPUS is a different, lower-intensity modality with distinct goals. JOSPT - Bottom line for the acute window: PBM and LIPUS can create a better “healing environment” while we keep you moving safely. They’re helpers, not replacements, for the progressive loading and movement practice that ultimately remodel tissue. PMC

2) Subacute phase (~1–6 weeks)

Goals: Restore motion, re-educate muscle activation, begin progressive loading.

Core plan

-

Gradual stretching and strength progression (isometric → isotonic → functional patterns), balance/coordination work, plus neuromuscular re-education training using motor control and motor learning principles.

Adjuncts we may use

-

NMES (neuromuscular electrical stimulation): when a muscle won’t “turn on” (e.g., quads after knee injury/surgery). Evidence supports improved early quadriceps strength when NMES is combined with exercise. JOSPTFrontiers

-

PBM (laser): can be layered for pain modulation (e.g., plantar heel pain) while you ramp up loading. JOSPT

-

Cupping: occasionally for short-term pain relief when irritability is low; always paired with active exercise. Frontiers

-

Ultrasound: routine use adds little for most MSK conditions; we generally prioritize active care. PMC

3) Chronic / remodeling phase (≥6 weeks → months)

Goals: Build capacity (strength, power, endurance), refine movement quality, and return to your goals (hiking, pickleball, lifting, job tasks).

Core plan

-

Progressive resistance training to near-fatigue with good form; graded exposure to real-world demands (increase one variable at a time: load, speed, or volume).

Adjuncts we may use

- High-Intensity, Low-Frequency TENS (HILF-TENS)

What it is: Also called acupuncture-like TENS (AL-TENS), this uses low frequency (~2–4 Hz) at high intensity (strong, near-tolerance) with a longer pulse width (≈100–400 µs). It’s designed to recruit A-δ afferents and engage endogenous opioid pathways for pain relief. PMCPubMed

Where we place electrodes: Often on tender points, motor points, dermatomal/mirroring sites, or low-impedance (acupoint) sites. Clinically, acupoint/low-impedance placement is common; however, when stimulation intensity is truly adequate, analgesia appears more dependent on dose than on skin impedance per se. We prioritize dose + comfort, then optimize placement. PMC -

Shockwave therapy (ESWT): for stubborn tendinopathies or plantar heel pain that haven’t responded to a solid loading program. Delivered in short sessions (commonly 1,500–3,000 shocks, spaced weekly, device-specific energy). We screen for contraindications (e.g., over lungs, in the shock-path of certain implanted devices, coagulopathy). shockwavetherapy.org, PMC

-

PBM: included for plantar heel pain in current guidelines; we still anchor care on loading, footwear/taping, and mobility. JOSPT

-

Cupping: may provide short-term pain reductions in chronic MSK pain; functional gains are less consistent—so we keep the focus on exercise. Frontiers

About Safety (how we keep things precise)

-

PBM (laser/LED): We follow WALT dosage tables by wavelength/condition (commonly in the 600–1000 nm range; energy windows set per tissue depth). Eye protection is mandatory; we avoid treatment directly over a fetus and over active cancer sites. Walt PBM+1Physiopedia

-

TENS: Used for short-term pain relief; safe for most people with proper screening. BMJ Open

-

NMES: We target a strong, visible contraction and progress to voluntary strengthening ASAP. JOSPT

-

Ultrasound: Minimal added value for many MSK conditions; not recommended for acute ankle sprains or to enhance stretching for plantar fasciitis. PMC, JOSPT

-

Cupping: Generally safe when properly applied; we avoid it over compromised skin and use caution with bleeding disorders/anticoagulation. NCBI

-

ESWT: Evidence supports use in plantar fasciitis and calcific rotator cuff when conservative care plateaus. We screen for contraindications (e.g., coagulopathy, shock path over lungs) and individualize parameters. shockwavetherapy.org, PMC

How We Progress You (our decision anchors)

-

Symptoms: pain during/after, swelling, morning stiffness

-

Function: gait quality, balance time, lift/carry tolerance, return-to-work/sport criteria

-

Tissue load tests: isometric response and next-day irritability

-

Context: your goals, health factors, sleep/stress

References

General soft-tissue healing & clinical frameworks

-

Dubois, B., & Esculier, J.-F. “Soft-tissue injuries simply need PEACE & LOVE.” Br J Sports Med (2020). (British Journal of Sports Medicine)

-

Gonzalez, A., Gupta, A. “Physiology, Wound Healing.” StatPearls (updated 2023). (NCBI)

Condition-specific clinical practice guidelines (CPGs)

-

Martin, R. et al. “Heel Pain—Plantar Fasciitis: Revision 2023.” JOSPT (2023). (JOSPT, APTA Orthopedics)

-

Martin, R. et al. “Ankle Stability and Movement Coordination Impairments—Lateral Ankle Ligament Sprains: Revision 2021.” JOSPT (2021). (JOSPT)

Photobiomodulation (PBM / “low-level laser”)

-

World Association for Photobiomodulation Therapy (WALT). Dosage Recommendations (accessed 2025). (Walt PBM)

-

Lawrence, J. et al. “Low-Level Laser Therapy (LLLT) for Acute Tissue Injury: A Review.” Biomedicines (2024). (PMC)

-

Huang, Y.-Y. et al. “Biphasic Dose Response in Low-Level Light Therapy.” (2009). (THOR Laser)

-

Morgan, R. M. et al. “Effects of Photobiomodulation on Pain and Return to Play of Injured Athletes: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.” J Strength Cond Res (2024). (PubMed)

Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS)

-

Xin, Z. et al. “Clinical applications of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound and its potential role in tissue healing.” Front Med (2016). (PMC)

-

Best, T. M. et al. “Low Intensity Ultrasound for Promoting Soft Tissue Healing.” Sports Med Open (2016). (PMC)

-

Fu, S.-C. et al. “In Vivo LIPUS Following Tendon Injury: Timing Matters.” JOSPT (2010). (JOSPT)

-

Li, Y. et al. “Effects of LIPUS in Tendon Injuries: Review.” J Ultrasound Med (2023). (Wiley Online Library)

Therapeutic ultrasound (conventional)

-

Matthews, M. J., et al. “Ultrasound Therapy.” StatPearls (updated 2023). (NCBI)

TENS (incl. high-intensity low-frequency / acupuncture-like TENS)

-

Vance, C. G. T. et al. “Using TENS for Pain Control: State of the Evidence.” Medicina (2022). (PMC)

-

Johnson, M. I. et al. “Efficacy and safety of TENS: Systematic Review & Meta-analysis.” BMJ Open (2022). (PubMed, BMJ Open)

-

Viderman, D. et al. “TENS for postoperative acute pain: Systematic Review & Meta-analysis.” J Clin Med (2024). (MDPI)

-

Sluka, K. A., et al. “Spinal blockade of opioid receptors prevents TENS analgesia.” J Neurosci (1999). (PubMed)

-

DeJesus, B. M. et al. “Effect of TENS on Pain and Central Sensitization.” J Pain (2023). (ResearchGate, ScienceDirect)

-

Chandran, C. G. T. V. (review) “Latest Advancements in TENS.” J Pain Res (2025). (MDPI)

-

Leonard, G. et al. “Increasing intensity prevents TENS tolerance.” J Pain (2012) & follow-up on alternating frequencies (2014). (Europe PMC, JPain)

-

Montenegro, E. J. N. et al. “Effect of low-frequency (acupuncture-like) TENS.” J Phys Ther Sci (2016). (PMC)

-

(On “low-impedance point” approaches) Biggs, N. et al. “Interactive neurostimulation at low-impedance skin points vs placebo.” J Bodyw Mov Ther (2012). (ScienceDirect)

-

Vance, C. G. T. et al. “Skin impedance is not a factor in TENS hypoalgesia when dosing is adequate.” Pain Med (2015). (PMC)

NMES for strength/activation with rehab

-

Kim, K. M. et al. “Effects of NMES after ACL reconstruction: Systematic Review.” JOSPT (2010). (JOSPT)

-

Hauger, A. V. et al. “NMES strengthens quadriceps after ACL surgery: Systematic Review & Meta-analysis.” Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc (2018). (Scholars@Duke, alfacare.no)

-

Peng, L. et al. “Post-op NMES after TKA: Systematic Review & Meta-analysis.” Front Med (2021). (Frontiers)

Extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT)

-

International Society for Medical Shockwave Treatment (ISMST). Guidelines for ESWT (Jan 3, 2024). (shockwavetherapy.org)

-

Tenforde, A. S. et al. “Best practices for ESWT in sports med clinics.” Am J Phys Med Rehabil (2022). (PMC)

-

Lippi, L. et al. “ESWT for plantar fasciopathy: Systematic Review & Meta-analysis.” Int J Environ Res Public Health (2024). (PMC)

-

Cortés-Pérez, I. et al. “ESWT vs corticosteroid injection for plantar fasciitis: Meta-analysis.” Muscles Ligaments Tendons J (2024). (PubMed)

Cupping therapy

-

Jia, Y. et al. “Cupping therapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain: Systematic Review & Meta-analysis.” BMJ Open (2025). (BMJ Open)

-

Kim, S. et al. “Is cupping effective for neck pain? Systematic Review.” BMJ Open (2018). (BMJ Open)

-

Furhad, S., Bokhari, A. “Cupping Therapy.” StatPearls (updated 2023). (NCBI)